Civil War Murals

112 Buchanan St

Cuba, MO

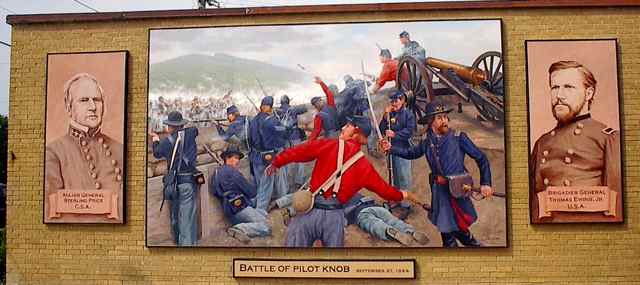

The tenth mural actually became a series of murals that told the story of the battle between the troops of Confederate General Sterling Price and Union General Thomas Ewing in September 1864. When Price’s troops came into Missouri from Arkansas, his original goal was to capture St. Louis or Jefferson City. However, he was distracted by the armory and ammunition at Fort Davidson in Pilot Knob, Missouri. The resulting battle of Pilot Knob and Ewing’s retreat from the fort are illustrated in two panels.

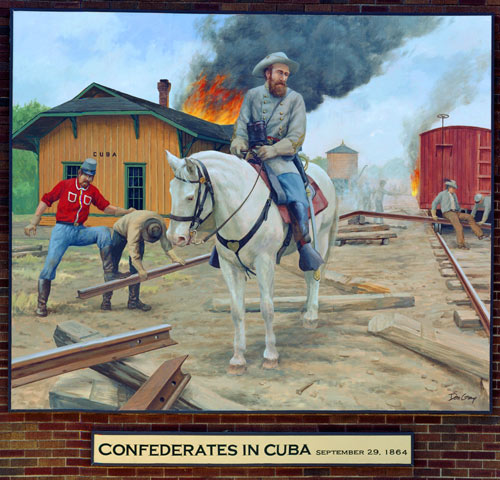

Another panel shows the Union troops fleeing across the Huzzah River while dodging rebel bullets on the way to Leasburg. A panel also represents the destruction of the depot and tracks in Cuba, thus preventing Ewing’s escape by train from Leasburg. The last panel depicts the dramatic rescue of Ewing’s troops at Leasburg.

Price’s troops were sent into Missouri, in part, to distract Grant and Sherman in the South from the fighting there. By creating conflicts west of the Mississippi, it was hoped that the generals in the South would have to send troops west to aid the Union troops. With elections coming up, the Confederates also wanted to destroy Union property, gain Confederate soldiers, and capture a major city. It was hoped that this would weaken the Union candidates in the elections.

With these goals in mind, General Sterling Price was sent with 12,000 troops, known as the Army of Missouri, to accomplish these goals. Instead of going directly to St. Louis, which was weakly defended, Price detoured to Pilot Knob, tempted by the arms and equipment, both of which he needed for his ill-equipped troops. He wouldn’t have minded capturing General Thomas Ewing, Jr., General Sherman’s brother-in-law. He had been sent to help defend Fort Davidson’s arms from falling into enemy hands.

Price’s troops foraged for food and fought local militia all over the Arcadia Valley, which consists of Pilot Knob, Ironton, and Arcadia.

Ewing had fewer than 1500 Union troops to hold off Price’s much larger force. However, Ewing’s men held off 6000 troops sent by Price for two days on September 26-27, but defeat seemed inevitable for the vastly outnumbered Union troops.

When General Ewing was faced with fighting to the death or surrender, he came up with a bolder plan. He would retreat under cover of darkness, caused in part by the shadows created by the mountains that surrounded the fort. After midnight, the drawbridge that covered the dry moat around the fort was lowered and covered with blankets and straw. The wagon wheels were wrapped, and the horses’ hooves were also shrouded in material. Ewing and his troops were able to thus slip quietly out of the fort. However, an even more amazing event was ahead of them.

To reach the Caledonia-Potosi Road it was necessary for Ewing’s troops to march between two lines of Confederates camps. Because of the darkness, Ewing’s men marched through enemy lines unchallenged. The camped Confederates thought other Confederate troops were marching on the road.

Ewing also sent a small detail back to the fort to plant explosives so that no ammunition or equipment would fall to the enemy. Gunpowder was placed around the buried ammunition magazine. The bodies of the dead Union troops were placed so that the explosion would bury them with earth, thus preventing scavenging Confederates from plundering their bodies. Setting the fuse, the small detail escaped after Ewing’s main troops. When Price heard the explosion, he thought it was an accidental explosion within the fort. He expected Ewing to surrender the next day.

When morning came, Price realized that Ewing had escaped and destroyed the fort. The chase was on that was to last 66 miles in 39 hours. Ewing hoped to reach a railroad where he could escape with his troops to St. Louis or Rolla. However, he was constantly forced to fight off rebel advances on his rear positions. One such battle occurred at the Huzzah River. A union soldier wrote of wading the river and being able to open is mouth for a drink while hearing the bullets hit the water like rain.

When Ewing reached Leasburg, then called Harrison Station, he loaded his troops aboard a supply train. However, he was to find out that Confederate troops had destroyed tracks at Cuba, burned the depot, and looted stores. A similar story had was told at Bourbon, so Ewing and his men had to disembark from the train at Leasburg and prepare to defend themselves from the approaching Confederate troops. Barns were burned to provide light so that the Confederates couldn’t attack across the fields at night.

The next day, the dust from the approaching Confederate horses was seen, and the troops prepared for battle. However, when the riders came closer, they realized that they were Union troops from Rolla, who had come to rescue them. There was much celebrating of civilians and soldiers alike. A flag that was made by a Mrs. Lea was waved and the group danced and sang, “Rally Round the Flag Boys.” The soldiers were escorted to St. James where they boarded the train to Rolla.

Price’s troops continued to march north, where they met defeat again near Kansas City at the Battle of Westport on October 23. Price and his troops were then driven from Missouri.

While the battles in Missouri depicted in these panels may seem small ones, they did help delay the action of Sherman in the South since troops had to be sent West to help with battle there. And Missouri battles did keep Price from accomplishing his mission and affecting the upcoming elections in favor of the rebel cause.

The Civil War series was a joint project between Viva Cuba, and 15 year-old Chip Lange, a young Civil War buff and re-enactor, as part of his Eagle Scout project. Chip Lange was involved in fundraising, which was matched by Viva Cuba ; researching; and preparing for the mural. To honor Chip’s role in the mural, artist Don Gray painted his face in the Leasburg panel. He is wearing a hat with a red band.

Artist Don Gray of California who has years of experience as a painter, muralist, illustrator, teacher, and has been involved in many public art projects painted the Civil War murals. See dongraystudio.com for more information.

Julie Nixon Krovicka painted the text panels.