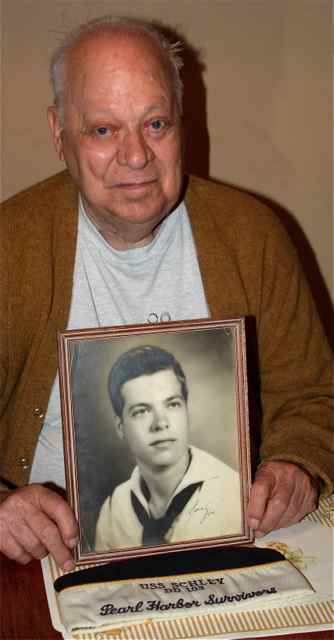

Remembering Cuba’s hometown hero, Joseph White, Jr. who passed away this week.

This information originally appeared in the Cuba Free Press in 2010.

Eighty-seven year old Joe Merrel White Jr. is a member of a rapidly shrinking band: survivors of Pearl Harbor. An eighteen year-old White was present December 7, 1941 when the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on what President Franklin Roosevelt would call “a date which will live in infamy.” Events of that day led to a declaration of war.

The Early Years

Joe White grew up during the depression, and he and his parents, two sisters, and a brother lived at 5743 Lotus Avenue in St. Louis. He went to Ben Blewett High School. During the depression he made spending money by selling newspapers, working on his uncle’s farm, and being a caddy.

While still a high school student and seventeen years old, he saw an ad in the St. Louis Star Times that stated, “Join the Naval Reserves and See the Great Lakes.” That was all he needed to heed the call to adventure and join the Naval Reserves.

Asked if he thought that he might be involved in a war because of the growing unrest in Europe at the time, he said, “Nope. I was just a kid. I wasn’t concerned with the world.”

Recently, at his country home in Leasburg, Missouri, he chucked when he said, “I did see the Great Lakes–twenty years later.” But his adventures were to go far beyond the U.S. and the Great Lakes.

Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1940

On December 7, 1940, White and 249 other officers and men were called up for active duty and ordered to be at Union Station in St. Louis on December 17, 1940. They were to travel on a special train and told to keep their shaving gear ditty bag out of their sea bag for the three-day trip and to have spending money for one month until their first pay day.

The Navy sent them to San Diego and then to Long Beach, where they boarded the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Lexington for transport to the Hawaiian Islands.

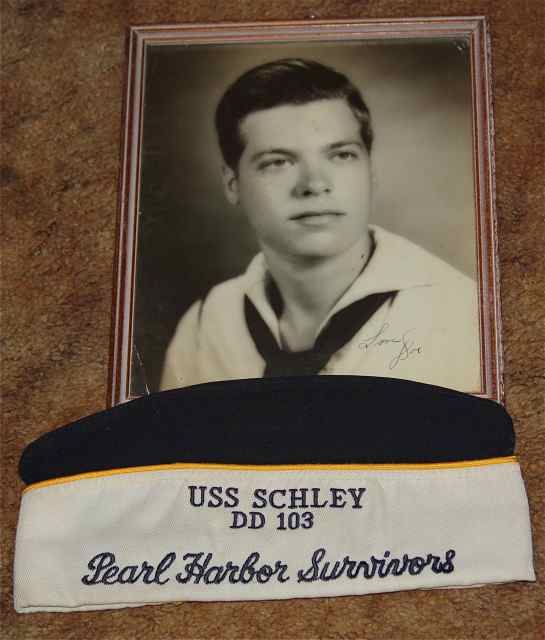

In the islands, White’s Thirty-Fifth Division was assigned to a W.W. I four-stack, 1060-ton destroyer, the U.S.S. Schley, built in 1918. Because of the mounting unrest in Europe and the Pacific, the Navy brought that ship out of mothball and re-commissioned it. His ship did picket duty for Pearl Harbor and patrolled between Diamond Head and Barbers Point, in site of Waikiki Beach. The Schley was one of four old destroyers, the U.S.S. Allen, the U.S.S. Schew, and the U.S.S.Ward, which shared picket duty.

While on patrol, on three occasions, they captured sampans in the restricted area. White was on one of the boarding parties. The sampans were turned in to the Coast Guard, and they later found out that the small boats were taking soundings.

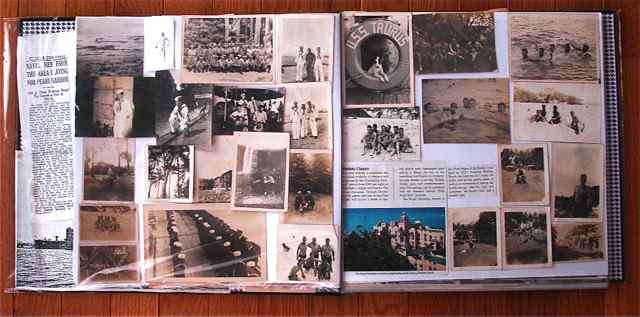

Honolulu wasn’t a bad posting for an eighteen year-old. The islands were a paradise, White’s scrapbooks show beach scenes, where the young sailors could swim. When he was in town, he went to the YMCA to sleep, and the soldiers bunked in private homes. The Black Cat Café was a hangout for soldiers.

White stated that the native Hawaiians liked the soldiers, but the white businessmen didn’t. He recalls a sign that said, “Dogs, Traveling Salesmen, and Sailors Keep Out.”

The U.S.S. Ward was on patrol December 7 when she sank a miniature submarine at 6:45 am. This would be the first shot fired in WW II. Their announcement of the submarine sinking was met with skepticism by the Command Post at Pearl, which told them that they were drunk and to go back and drink another bottle. This was about an hour before the first Japanese bombers arrived.

White recounts his activities that fateful Sunday morning on December 7, 1941 when he was on a weekend pass in Honolulu and staying at the YMCA. He heard the first wave of bombings and thought it was strange that the batteries at Schofield Barracks were firing so early. “ I was on the steps of the Catholic Church getting ready to go to 8:00 mass when I heard squealing bus tires behind me.” White was told to get on the bus for return to his ship because they were being attacked.

On the way to the harbor with other soldiers who had been rounded up, there was chaos on the roads. The panicked civilians were running from the scene, and Navy personnel were trying to get to their stations. “We had to travel on the shoulder of the road to the harbor,” said White. The first wave of bombers had already completed their runs when White arrived at his ship.

“On our arrival, we were strafed by a low flying Japanese plane, and as I looked up, the gunner thumbed his nose at us.” This was the second wave of Japanese who attacked at Pearl Harbor.

The Schley and some other ships were moored in the Southeast Loch for refitting, and their view of the harbor was blocked by two cruisers the St. Louis and the Honolulu, which was damaged by a bomb that flooded part of the ship.

Because of the overhaul, the Schley was unarmed, so the gunner’s mate broke into a locked storage shed and came back with a 50-caliber machine gun and ammunition. “I loaded the belt with ammo while he fired the gun. They were old W.W. I shells and many of them were duds.” According to White, firing from both ships and individuals filled the skies, but he doesn’t remember hearing sirens like the movies often depict.

That night White remembers being given a gun and put on picket duty on a totally dark wharf. He was all by himself and couldn’t see or hear anything. He was supposed to be watching for Japanese saboteurs.

The Pearl Harbor military statistics are sobering: 2335 killed, 1143 wounded, and that doesn’t include the 68 civilians who were killed and the 35 who were wounded. Eighteen ships were sunk or seriously damaged, and 347 planes were destroyed or damaged.

White still has a Western Union telegram that was delivered to his parents on Lotus Avenue in St. Louis that states “Men in whom you are interested not reported to have sustained injury or casualty aboard Schley–Bureau of Navigation Navy Department.”

The Duration of the War

Ironically, when war was declared and the draft for 19-45 year olds was instituted, Joe White could have gone back home and returned to school because he was only 18. However, White felt that he was in the war for the duration.

White and his fellow sailors rushed to get the Schley seaworthy in the next week and to get her back on duty again running picket duty for Pearl Harbor. After serving well and receiving eleven battle stars, the Schley was scrapped in 1945.

In June of 1942, White was on R & R at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. Then he was transferred back to the states, and his new ship was a cargo steamer from the United Fruit Co., the San Benito, built in 1921. The ship was commissioned into the U.S. Navy as the U.S.S. Taurus AF25. After many repairs, they sailed to New Zealand, which would be their homeport for three years. The Taurus was a refrigerated supply ship that supplied the Marines when they established beachheads. The Taurus helped feed the islands during the war and was often near the site of battles.

During these days in the islands and lands around New Zealand, the young man from Missouri experienced some memories that still stand out today.

*When they arrived in Caledonia, the French had mistakenly scuttled their ships to keep them out of enemy hands, which was, in this case, the newly arrived Taurus.

*White went to Sunday mass in a leper colony, with a railing separating the sick and the well.

*On an island, they traveled up a river and saw bats with a two-foot wingspan. They came to a garden and proceeded to pick fruit–limes, lemons, and papayas. A very irate native came running out with a sword screaming they were stealing the Queen’s fruit. They left.

*When they arrived at Guadalcanal, all the palm trees were topless from the bombing. There, they took the dead Marines’ sea bags back to Auckland. The next trip they took exhausted marines back for R & R.

* The Taurus anchored over a ship that was sunk the previous night, and dead bodies surfaced throughout the day. Across the channel, trenches were dug with Japanese piled up like cordwood beside them.

*At one docking at Bougonville, they were just out of range of the Japanese shore batteries. The spray of water from their shells was hitting White as he was painting the bow of the ship.

After the War

White was mustered out of the navy November 20, 1945 after spending fifty-four months overseas. He was twenty-two years old. In 1948, he married his wife Loretta, and they raised three daughters and two sons. He spent 1 ½ years at Missouri University on the G.I. Bill, worked for Wagner Electric, was a 4th generation railroad worker for the Terminal Railroad, and also worked for the Chevrolet plant in St. Louis. In 1971, he and his wife, who was from the Leasburg area, built the Coachlight Inn (now Skippy’s) and ran it for 17 ½ years. White designed and built his country home in Leasburg where he still lives. His wife passed away two years ago.

Today, he has his scrapbooks of those days during the war that helped forge a young Missouri boy into a man. Someday, they will belong to his children. He is a member of the Missouri Chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, whose membership has dwindled to a handful. White never returned to visit the Hawaiian Islands, but he is very much aware of the part that he played in the history of the islands and the United States. The motto of the Pearl Harbor Survivors is Remember Pearl Harbor—Keep America Alert.

When he is asked what he wants people to remember about the attack on Pearl Harbor, he says, “It wasn’t like the movies. A lot of what you see is just bull.’ He said he only watched half of the movie Pearl Harbor although he did concede that the movie Tora, Tora, Tora was more accurate.

While White may be walking slower these days, he is a part of history, and we can revere and recognize him for his part in a generation of Americans who grew up in the midst of sacrifice and unrest but still retained their humor and American “can do” attitude. After paying their down payment on Freedom, the survivors of the greatest generation would come home, marry, find jobs, build homes and lives, and raise their families. Joe White is a representative of that generation.

Joe White was interviewed for this piece. An essay written by his daughter about his experiences for the Veterans History Project of WW II was also used as a source as was the collection of articles and artifacts in his personal scrapbook. Life’s Pearl Harbor American’s Call to Arms (editor Robert Sullivan) provided background information.

Joe White had not idea what lay in store for him when he signed up for the navy. He changed from an inexperienced kid to a military man who would travel the world.

Fascinating reading. My father, George A. Stevens was stationed on the USS Taurus during WWII. George, or “Stinky Stevens”, as nicknamed by crewmates after being caught under a flushing toilet (while sneaking back aboard ship), served with Mr. White.

Thanks for the great anecdote.

This is my father, he rarely talked about his time at Pearl Harbor. Thank you for sharing this article.

Barbara, is your father still alive? I hope so, as I will be mailing a Christmas letter to him with pics of my dad who served with him on the SS Taurus. I guess if I get the letter back then I can assume your dad has passed on and maybe reminiscing with my dad (who passed in 1992) about their time in the Navy.

The address at the St. James Veterans Home is correct for 2015.

Yes, Lori, my father is alive and living at the VA in St. James, Missouri. He would enjoy receiving a Christmas card from you.

Fantastic ! Thanks so much for the good news. I’ll start on that card now and include photos of my dad from the Navy. I’m betting they knew each other. FYI: my husband was born in Nyehart Junction and grew up on a farm in Butler, Missouri. His parents were sharecroppers.

That’s great, I don’t think there are a lot of Pear Harbor survivors at the St. James VA. Lori, is your father still alive? My dad was 17 when he enlisted in the Navy.

My sister and I have a family tree on Ancestry and hope we can find my dad’s grandfather. I will have to google Nyehart Junction and Butler, Missouri to see where it is located.

Hi Barbara,

Sadly, my dad passed away in 1992. My oldest sister is doing our mothers family tree on Ancestry. She’s got parts of our family going back to 800 A.D. and some before that. I’m doing my father’s family and then we’re combining it all. Genealogy is great, as it documents all our loved ones, where we came from, for future generations. But it is time consuming. Good luck on your tree!

We were told that Mr. White received many Christmas cards from posts about him on Social Media.

Great stories! What rate was Mr. White? I assume he might have been a Petty Officer but what was his duty specialty?

We have a Springfield M1903 rifle at our local veterans museum here in Huntsville, Alabama that was aboard the Schley on 7 December. I am writing a story about it for the upcoming 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. We also just honored another sailor who was assigned to Pearl Harbor and lives in a retirement home here. He just went to Pearl Harbor with his daughter—-the first time since he was there during the war.

http://whnt.com/2016/09/04/wwii-veteran-has-flag-pole-installed-at-his-apartment-complex-after-lobbying-for-it-for-8-years/

The Honor Flights are a wonderful for the greatest generation are a great tribute.

Sorry, we do not have that information. Perhaps some of Mr. White’s family will see this an reply.

My Father Joseph White was a Petty Officer 2nd Class.

Thanks for your update.

My father, WILLIAM DON CROLEY was on the Schley between May 1940 and March 1942.

He passed in 1972 and I never had the opportunity to speak to him of his 20 years in the navy.

Hi Barbara,

Yes, my Dad Joseph White was also on the Schley. It was in Pearl Harbor during the attack. He stayed in the Navy till 1945, but was transferred to another ship after Pearl Harbor and spent time in New Zealand. Dad will be 95 next month. I have his Photo album from his Navy days. I’ve also been in contact with another shipmates daughter. Would be happy to share papers I have. Sorry of your Dad’s passing. Cindy

It is nice to see the connections being made between family members. Thanks for the update on your dad Cindy. I often think of him.

Your welcome Jane. Dad will be 94 in a couple of weeks. In my reply to Barbara, I said 95. He is doing well and I hope he will receive Birthday Cards again this year. Thanks for keeping up with him through the years.

You might repost his address here.

My Dad is living at the Veterans Home. His address is: Joseph White: Mo. Veterans Home

620 North Jefferson

St. James, Mo.

65559

My father, Earl Wanbaugh, is also a Pearl Harbor survivor aboard the USS Pennsylvania. He is 99 and still lives on his own in Independence, MO. As far as I know your father and he are the only survivors left in Missouri.

Hi Linn,

It’s Great your Dad can live on his own at 99! I visited with my Father today and told him of your Dad. I knew there were very few survivors left. The Pearl Harbor Survivor meeting’s stopped in 2011. I’ve asked at the V.A Home how many actually were still alive. They didn’t know. But my Dad is the only one in this area. Tell your Father Thank You for his service. Joe’s Daughter, Cindy

Thank you for doing everything you do! I find it to be admirable and inspiring! Again…. thank you!

My father Joseph White will be turning 97 this weekend.

My father Joseph M. White Jr. Passed January 18,2021. Peacefully in his sleep. He will be buried at Jefferson Barracks.