The Gold Star Boys

402 W Washington Street

Cuba, MO 65453

The Gold Star Mural just off Route 66 in Cuba was painted just after 9/11 although it had been planned for months. With its tribute to the young men from the Cuba area who had lost their lives during WWII, it seemed an apt expression of the feeling of patriotism that swept the country at the time.

The train in the mural is The Blue Bonnet. During W.W. II the Blue Bonnet, a Frisco train named after the Texas state flower, was a familiar sight with its distinctive blue and white cars. It was this #7 train that whisked away Cuba’s service men as they left their homes to protect America’s way of life and values. These young men sometimes gave their lives to keep the light of freedom burning.

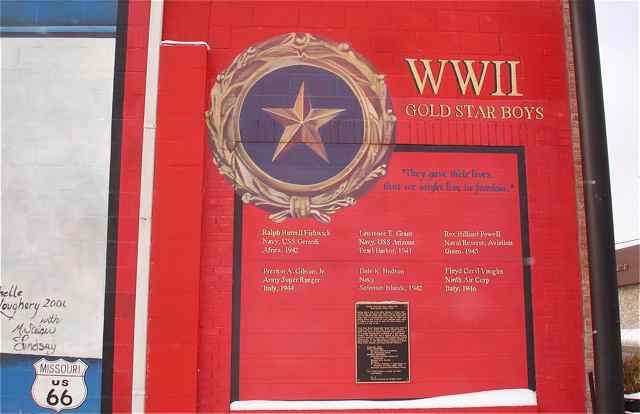

Cuba’s Gold Star boys who gave their lives during WW II were the following: Ralph Burnell Fishwick-Navy; Preston A. (Bud) Gibson Jr.-Army; Lawrence E. Grant-Navy; Dale K. Hudson-Navy; Rex Hilliard Powell-Naval Reserve; and Floyd Cecil Vaughn-9th Air Corps. Their names on listed on the red background on the north end of the mural. Their names can also be found on the Cuba Veterans Memorial on Smith Street.

According to a Cuba Free Press letter to the editor at the time the mural was painted, Wilbur Vaughn remembered his family taking his brother Cecil to this train during World War II. He then went home, sat on the porch, and heard the whistle of the Blue Bonnet as it left. He remembered how sad it sounded. His brother Cecil Vaughn is one of the young men who did not return from the war.

You might wonder why these men who died in the service of their country were called “Gold Star Boys.” With Public Law 534, the 89th Congress directed the design and distribution of a lapel button–known as the Gold Star Lapel button–to identify widows, parents, and next of kin of members of the Armed Forces of the United who lost their lives during hostilities. The pin is depicted on the north end of the mural.

The pin, which is issued by the Department of Defense, is gold and is on a purple background for combat death and all gold for death while in service. When one of the service men was killed in combat, his relatives received this gold pin. Service men’s mothers often wore the medal to show that they had lost a son. It was a badge not only of sadness for loss but also one of pride because their sons had sacrificed for their country.

Viva Cuba would like to remember these young men and all the young men and women who have served their country both in time of peace and in time of war.

For more information on the Gold Star Mothers’ organization, visit goldstarmoms.com.

The Artists…

Michelle Loughery, of Canada, who painted the A.J. Barnett mural, along with her assistant Sara Lindsay, returned to Cuba for this mural. Local artist Shelly Smith Steiger assisted on the mural.

Then Viva Cuba found out that there was more to the story in respect to one of the young men, Ralph Fishwick, who is pictured in the mural. Ralph Fishwick was born in Cuba in 1912 and on his father’s side of the family was a member of one of the early families of Cuba that was involved in mercantile and banking. On his mother’s side of the family, he was related to the Bishs. In 1930, after he graduated from Cuba High School, he wanted to join the Navy. He was told that his eyes were bad and rejected. He was suggested that he practice eye exercises if he wanted to try again. After faithfully doing the exercises, he was accepted and began his first tour of duty. Shortly after that, his eyes worsened, and he started wearing glasses.

In the Navy he received training to become an electrician. After his tour of duty, he returned to Cuba. When World War II broke out, Fishwick re-enlisted. When his convoy went down off the coast of Africa, his family was notified that he lost his life on December 2, 1942. When Viva Cuba researched the mural and found an early publication about WWII soldiers, this version of his military duty along with a photo in the book was used in the mural’s design. In the red border of the mural the names of the six young men are inscribed along with the location where they died during the war. At the time of the mural painting, Viva Cuba thought this information to be accurate. But it wasn’t. Read on for the rest of the story.

What was revealed . . . About 20 years ago, Mr. Fishwick’s niece Carol contacted the Defense Department after discovering that certain papers about his death had been declassified. What his niece found out was quite different from what the family had been led to believe.

Mr. Fishwick had died when his small boat was hit by a mine or perhaps by a German submarine off the East coast of the United States. As a matter of national security, the United States government didn’t want anyone to know that an enemy submarine could be that close to an American coastline. So, the story was changed when the families were notified.

Ralph Fishwick’s body along with 14 others was discovered off the East coast of the U.S. on May 8, 1943. The cold waters of the Atlantic had kept their bodies perfectly preserved. He was brought back and buried in Kinder Cemetery alongside many members of the Fishwick and Bish families.

The new version of Ralph Fishwick’s story was related during the 2011 Cuba Fest Cemetery Tour that takes place in Kinder Cemetery. Brad Austin portrayed Ralph Fishwick.

Because Mr. Fishwick died while he was in the service, he is known as a Gold Star boy. A Gold Star pin was given to his mother, showing that she had lost a son. It was worn with pride but also with a sense of loss and sadness. When the mural featuring Fishwick was painted, his brother bob felt pride that Ralph Fishwick was included in the remembrance.

So, the next time, that you are in the area of the mural on Filmore Street, stop and pay tribute to all Cuba’s brave young mem who are pictured in the mural. You will also find their names with a star by them etched on the Veterans Memorial on N. Smith Street. In the Recklein Commons Area. And that’s the rest of the story.

[…] https://cubamomurals.com/wordpress/2010/05/the-gold-star-boys-mural-remembers-sacrifice/ […]

[…] https://cubamomurals.com/2010/05/the-gold-star-boys-mural-remembers-sacrifice/ […]

There also was a ‘flag’ to hang in your window with a star for every member of your family that was in military service. Some Cuba families lost more than one member.